Performances at The Britannia, Hoxton: replaying The Octoroon

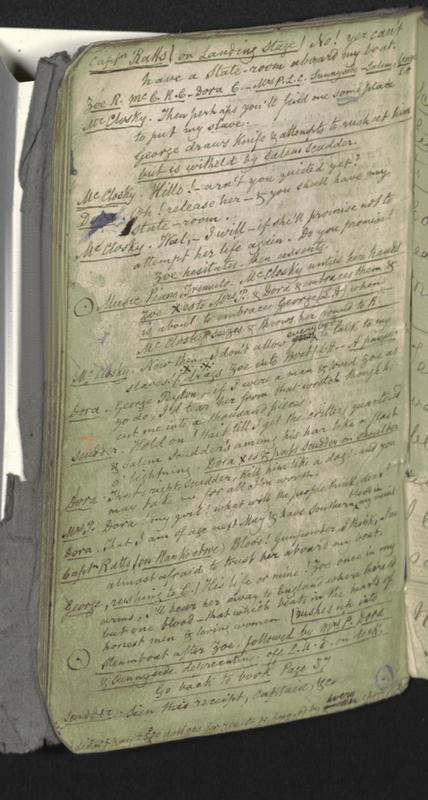

At the University of Kent, in Canterbury, England, we have discovered an Octoroon promptbook belonging to Frederick Wilton, an actor and stage manager of the Britannia Theatre in London's East End from 1846 to 1875. Wilton's promptbook is playfully inscribed, "F. Wilton hys boke July 5 1871."

This prompt book consists of Lacy's printed four-act script of The Octoroon, (in which the heroine neither kills herself, nor marries her white suitor, George, but appears silently in his arms in a concluding tableau), into which numerous pages of handwritten annotations are added. As we noted above, in this printed four-act version, the printed pages of the script conclude with stage directions that merely state that "George enters, bearing Zoe in his arms--all the characters rush on." Characters watch as the steamboat Magnolia explodes onstage, along with this spectacular stage effect, they form a "grand tableaux," that is followed by the "Curtain." The stage directions here do not specify whether Zoe is alive or dead, but in this version there is no suicide scene, so audiences may assume Zoe was rescued by her lover, in whose arms she appears.

However, Wilton's promptbook contains additional pages after the printed four-act script, and includes handwritten notations inscribed in at least two obviously different hands that, along with the printed script, account for three or four different possible endings. Inscribed in ink on pages 6-7 is the notation "Time, first night, own benefit, July 5, 1871, Act 1 began 9:30 . . . Act 4 ended 11:57 total 2h. 27m."

According to the notes written onto the otherwise final blank pages, this version of The Octoroon concluded when George rushed onto the boat where the evil overseer, M'Closky has taken Zoe, after “purchasing” her at a slave auction.

Crossing to center stage, George attacked M'Closky while proclaiming "His life or mine! Zoe once in my arms, I'll bear her away to England where there is but one blood--that which beats in the hearts of honest men & loving women." This line echoes, almost exactly, the published reports about Boucicault's "new" British ending performed a decade earlier.

On subsequent pages in this same promptbook, a copy of Act V of the original New York version of the play, in which Zoe dies is written in an entirely different handwriting. Written into this version is the final scene where Zoe committed suicide, speaking the exact lines uttered in the last act of Boucicault's original American version, thus establishing that in subsequent British productions, the heroine resorted to suicide as she did in the original productions.

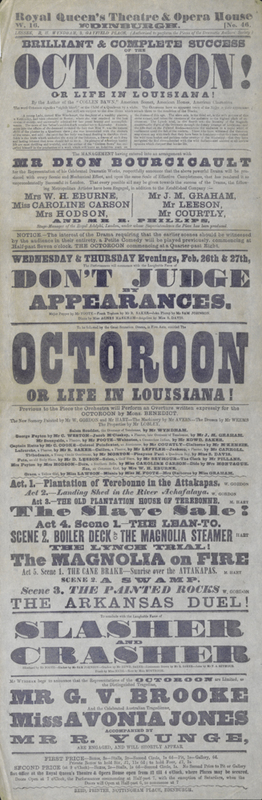

The playbills in this digital archive represent a sample of the multiple endings and formats we found in which the play was produced and expressed contradictory attitudes about enslavement.

In one, a playbill from Royal Queen's Theatre and Opera House Edinburgh, February 26 and 27, 1862, just months after the London premier of Boucicault's "rewritten" version where Zoe survives, announced "[t]he great sensation drama in five acts entitled the Octoroon."

This playbill features an account of a purported "true story" of a Miss Winchester who, like the fictional Zoe, was described as "the natural child of the planter by a quadroon slave; she was inventoried in chattels of the estate and sold; the next day her body was found floating in the Ohio river." The playbill declared, "[s]uch is the truth which underlies the story of the Octoroon.” Presumably, the production of The Octoroon advertised in this manner would feature a mixed-race heroine who commits suicide but the scenes listed on the same playbill also include the duel that Boucicault introduced in the final act in the version in which Zoe survived. Our finding that elements from both US and British versions of the play were contained within the same playbills and promptbooks complicates previous critics' assumptions that disparate versions of The Octoroon produced in each locale participated in debates about race and slavery at this time of racial terror.

Finding multiple endings suggests that Britain was caught in a complex and indeterminate web of attitudes about racial identities, and there may have been an awareness on the part of some theatrical producers and spectators that British notions of liberty and justice did not necessarily result in revised "happy endings" for enslaved persons.

In fact, we argue that our archival findings reflect the very mixed messages about race and empire, desire and hybridity that were then operative in the metropole. As the Civil War raged in the US and in the years that followed, while various versions of The Octoroon were being staged concurrently, questions of whether any version of this drama advocated the abolition or the proslavery cause continued to fuel uncertainty and fill theatres. However the play concluded in Britain and America, The Octoroon complicated notions of racial binaries and spectator sympathy.